Scientists drill first deep ice core at the South Pole

UCI and fellow researchers map climate history at the bottom of the Earth

This winter, when many people’s imaginations were fixed on the North Pole, a small group of glaciologists has been working in round-the-clock daylight and frigid temperatures drilling an ice core at the other end of the planet.

Drilling continues through the end of January for the first of two years of a joint project by the UC Irvine and the University of Washington. The National Science Foundation is funding the South Pole Ice Core Project to dig into climate history at the planet’s southernmost tip.

The 40,000-year record will be the first deep core from this region of Antarctica, and the first record longer than 3,000 years collected south of 82 degrees latitude. Scientists were attracted by conditions at the pole, which are cold even by Antarctic standards.

“This is basically the coldest ice that we have drilled in,” said principal investigator Murat Aydin, a UCI researcher and chief scientist from field camp setup in early November through December. “Everything is harder.”

“The cold temperatures in the ice, about -50 C, have caused some surprises with drilling since certain aspects of the drill perform differently even than during the test in Greenland at -30 C,” said T.J. Fudge, a UW postdoctoral researcher who is chief scientist this month.

There are good reasons to drill in these especially frigid subzero temperatures.

“Most of the other places where we’ve worked the ice is -25 C to -30 C, and that’s too warm for rare organic molecules and other trace gases that our colleagues are interested in measuring,” said co-leader Eric Steig, a UW professor of Earth and space sciences.

The location is just 1.7 miles from the South Pole. The thick, uncontaminated layers of ice there will help answer questions about how Antarctic climate interacts with the rest of the world. The period between 40,000 years ago and 10,000 years ago includes sudden swings in temperature, ending with warming at the end of the last ice age.

All three scientists were part of a team that collected a more than 2-mile ice core from West Antarctica, a five-year effort that ended in 2011. Analysis of that ice is ongoing at UCI, UW and many other labs nationwide.

“The South Pole is part of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, yet is influenced by storms coming across the West Antarctic Ice Sheet,” Fudge said. “This core will help us figure out how the two sides of Antarctica communicate during climate changes in the past.”

The project at the South Pole is using a new intermediate-depth drill based on a Danish design that is lighter than the one used in West Antarctica. A new drilling fluid is also being employed. The team reached a depth of 1/3 mile on Jan. 14. Researchers hope to near a one-mile depth by the end of next season.

“We’re not just trying to punch through the ice sheet; the most important objective is to bring up the highest-quality ice possible,” Aydin said.

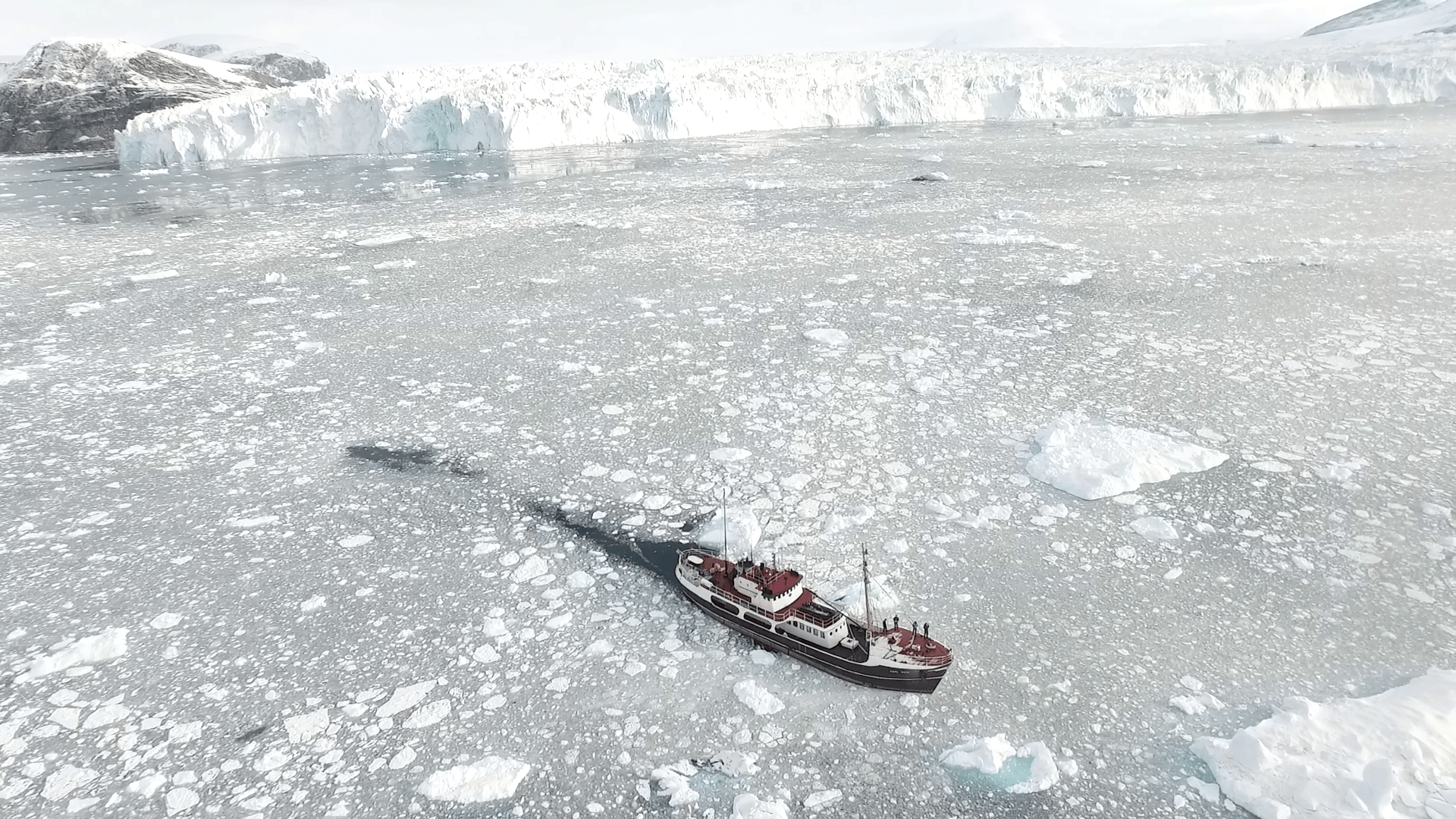

After the core is drilled, three-foot sections will be flown to McMurdo Station and transferred to a ship. Scientists will then converge on Denver’s National Ice Core Laboratory this summer to process the samples and ship pieces to labs across the country.

In UW’s IsoLab, Steig will analyze different types of oxygen molecules in the ice to determine the temperature. This will provide a record of climate changes for that region and help to evaluate the large-scale climate patterns across the Southern Hemisphere.

“The South Pole is one of the very few places in Antarctica that has not warmed up in the past 50 years,” Steig said. “That’s interesting, and needs to be better understood.”

The UCI group will look at ultra-trace gases from air bubbles trapped in the ice. Aydin is interested in gases that are one-in-a-billion to one-in-a-trillion molecules in the atmosphere, but provide clues about the productivity of land-based plants and the extent of tropical wetlands in previous eras.

So far, looking at the core shows one layer of ash that the researchers think is tied to a volcanic eruption in the South Sandwich Islands.

“Otherwise, the core has been beautifully clear,” Fudge said.

Scientists work inside a field tent at about -20 C, the same temperature as the national ice core lab. Extra-curricular highlights of this year’s season, chronicled by UCI graduate student Mindy Nicewonger on her blog, included the Christmas Day round-the-world running race, and participating in the New Year’s annual marking of the South Pole.

Partners on the project include the University of New Hampshire and NASA. This season’s field team includes Kimberly Casey at NASA; David Ferris at the University of Dartmouth; Nicewonger and members of the U.S. Ice Drilling Design and Operations group. The NASA team includes Thomas Neumann, a UW graduate and affiliate professor in Earth and space sciences.