Hunting for cures to hair loss

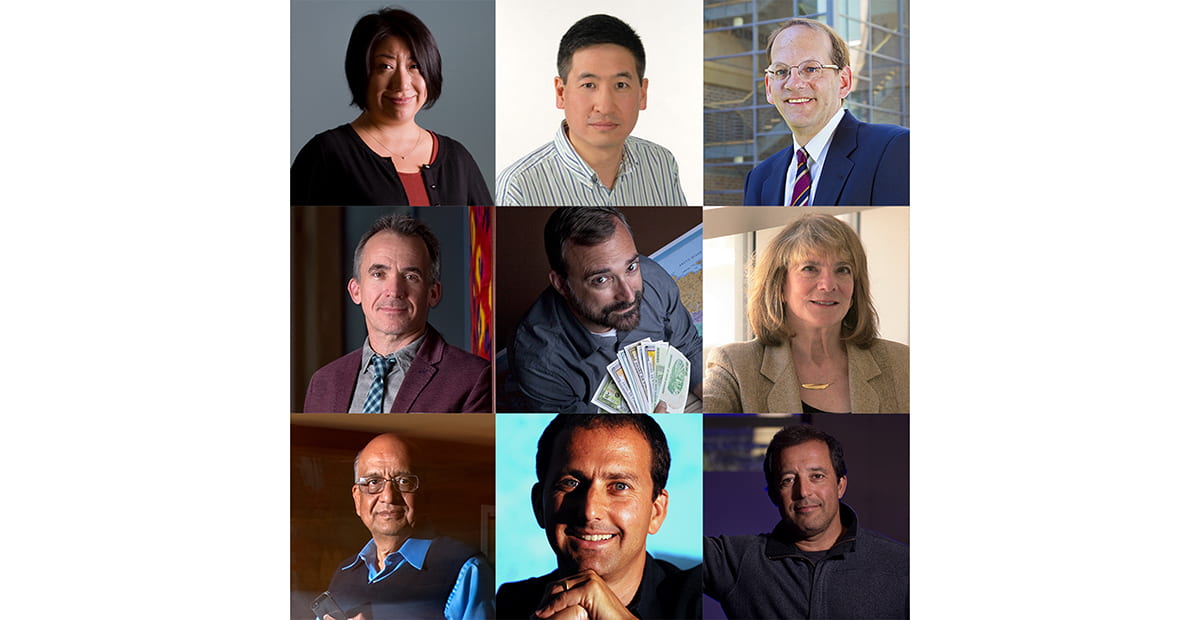

UCI’s Natasha Mesinkovska and Maksim Plikus garner national attention as leaders in the field

Dissecting rat whiskers as a teenager led Maksim Plikus into baldness research. Seeing children devastated by severe hair loss spurred Dr. Natasha Mesinkovska’s quest for a remedy.

Although they tackle the problem of thinning manes from different angles – Plikus as a laboratory scientist and Mesinkovska as a dermatologist treating patients – their efforts have helped make UCI a leader in the field, from bench to bedside.

“Hair is the next frontier,” Mesinkovska says.

But it’s cloaked in mystery. What makes locks curly versus straight – or an eyelash different from the hair in a beard or a ponytail? “Nobody knows for sure,” Plikus says. “There’s a lot we still don’t fully understand.”

In a Zoom interview, he and Mesinkovska discuss research obstacles, hair enigmas, dubious baldness elixirs and promising new findings, including Plikus’ discovery of a molecule that revived dormant follicles in mice.

Much of a person’s self-image is tangled up in tresses, says Mesinkovska, an associate professor of dermatology at UCI and former chief scientific officer of the National Alopecia Areata Foundation, which combats hair loss disease. A healthy mane signifies youth, beauty and vitality, she adds.

So when it falls out, the emotional impact can be dramatic.

“People plead to be in our clinical trials,” says Plikus, a UCI professor of developmental and cell biology who worked in a Los Angeles hair transplant clinic – where grafts from the back of a person’s head are moved to the top – before deciding to get a Ph.D.

But such studies are rare, partly because federal agencies are tightfisted when it comes to funding baldness research, Mesinkovska says. Hair disorders aren’t fatal, so they’re not a top priority, Plikus explains.

Another problem is that mice, the most common laboratory test subjects, are poor stand-ins for people. For starters, their fur is unaffected by testosterone, which plays a powerful role in human hair growth (and loss), Plikus notes. Rodent hair is also much shorter, so even if a treatment successfully resurrects mouse fur, there’s no guarantee it will work similarly on people, he says.

“We want strands that imitate the original color, length and curvature of a person’s hair,” Plikus says. “But we can’t promise what the new growth will look like. Pigment is especially difficult to reconstruct.”

The same follicles that produce blond hair in a baby might later sprout dark locks, he adds: “How it switches, we don’t know. It’s fascinating.”

To get around the gulf between experimenting on mouse versus human hair, some researchers have tried to grow the latter in petri dishes. But the lab version lasts only a few days, Plikus says.

Others, including UCI scientists, often use computer models based on digitized data from human tissue. “We have cartoon hair growing on a computer screen,” Plikus says.

Mesinkovska has employed artificial intelligence in some of her research. She also recruited patients for a recent New England Journal of Medicine study in which a rheumatoid arthritis drug reversed hair loss in nearly 40 percent of people with severe alopecia areata.

“My life’s passion is how to grow hair, how to keep the hair we have on our head and how to make it look good,” says Mesinkovska, a Yugoslavia native who moved by herself to the U.S. at age 16, earned a Ph.D. and an M.D., and has co-authored more than 50 scholarly papers on hair loss.

“There are so many things out there that promise to restore hair – from shampoos and gels to devices, lights and helmets,” she says, adding that most are “snake oil” or based on questionable research. Attempts to clone or 3D-print new hair haven’t yet succeeded.

One treatment with mixed results involves implanting laboratory-cultured hair cells in a person’s scalp. The results last about nine months, Mesinkovska says. And the procedure isn’t cheap.

Last year, Plikus made international headlines after his team discovered SCUBE3, a natural protein molecule that restored hair growth in bald mice.

Plikus co-founded a biotechnology company, Amplifica, to potentially commercialize the breakthrough. Most likely, SCUBE3 would be microinjected less than a millimeter beneath a person’s skin, a “fairly painless” process that would have to be repeated periodically to maintain hair growth, he says.

Human trials on the company’s lead compound are expected to begin later this year.

If you want to learn more about supporting this or other activities at UCI, please visit the Brilliant Future website at https://brilliantfuture.uci.edu. Publicly launched on Oct. 4, 2019, the Brilliant Future campaign aims to raise awareness and support for UCI. By engaging 75,000 alumni and garnering $2 billion in philanthropic investment, UCI seeks to reach new heights of excellence in student success, health and wellness, research and more. The School of Biological Sciences and School of Medicine play a vital role in the success of the campaign. Learn more by visiting https://brilliantfuture.uci.edu/school-of-biological-sciences/ and https://brilliantfuture.uci.edu/uci-school-of-medicine/.